In 1938, psychology pioneer (and infamous eugenicist) Lewis Terman first showed that premarital sex is strongly correlated with marital instability, with more partners generally associated with more divorce. Since then, many scholars have replicated this finding. What’s less well known is why. Without much evidence, many social scientists have concluded this association can be attributed to sample selection: the kinds of people liable to have a lot of sex partners are the same kinds of people who will get divorced. Of course, there’s an alternative possibility: the experience of having premarital sexual partners might change people’s beliefs or behaviors in ways that make it harder to sustain a marriage later on.

The best of these studies, from sociologists Joan Kahn and Kathryn London, used data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), and a statistical model that showed that sample selection could account for the relationship between being a virgin and the likelihood of divorce. But their study only contrasted virgins with people who had previously had sex, and didn’t seek to identify the specific mechanisms driving the selection. Their paper is also more than 30 years old, and only looked at white women. In 2016, Nick wrote an IFS post that used recent NSFG data to explore how different numbers of sex partners affected women’s marital stability, but didn’t try to explain why premarital partners increased the chances of divorce.

The time is therefore right for research that seeks to explain the premarital sex-divorce relationship using recent data. This was the basis of a paper we just published in Journal of Family Issues. Using data on both men and women from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), we revisit the effects of premarital sex partners on marital stability. We sought to test the sample selection argument by using a welter of the variables commonly identified as the basis of the selection, including religiosity, sexual attitudes, and psychological attributes. We also explored whether having many multiple premarital sex partners results in incrementally higher divorce rates.

Our results suggest that none of the commonly theorized explanatory mechanisms can account for the relationship between premarital sex and divorce rates. We don’t rule out the possibility that selection is driving our results, but lay down a marker for future research: scholars will have to look elsewhere in explaining why premarital sex makes divorce more likely. We also find that having nine or more partners produces higher divorce rates than having less than that. Finally, we show there’s no gender difference: premarital sex raises the divorce rate for both men and women.

We’re not aware of earlier research that’s used the Add Health data to look at premarital sex and divorce. Add Health, a panel data set with a large initial sample, contains much more detailed information about respondents than is available in the cross-sectional National Survey of Family Growth. 1

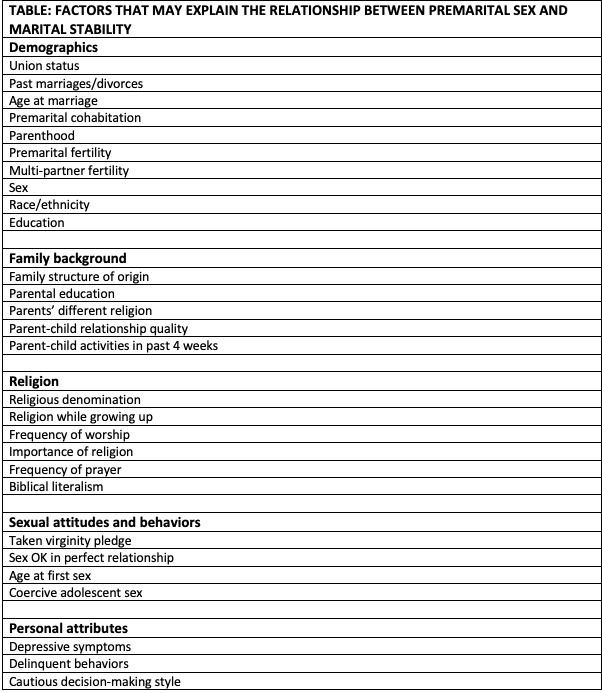

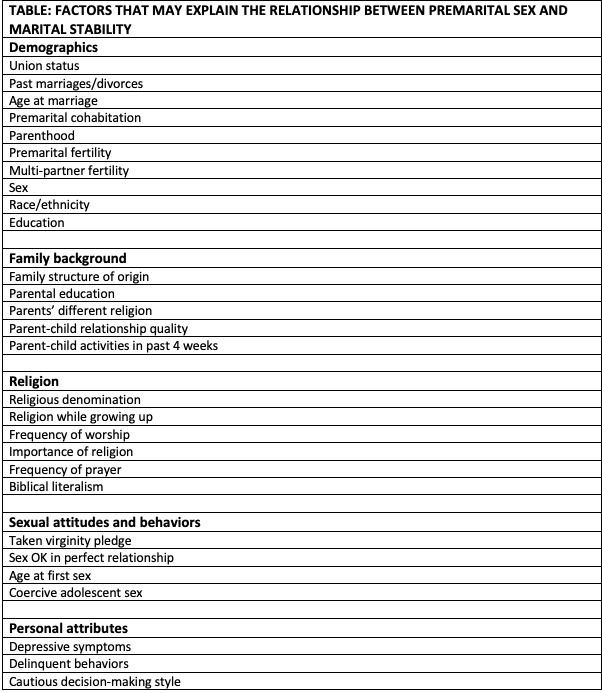

The table below shows the wide range of variables we used to try to explain the relationship between premarital sex partners and divorce. Do any of them matter? The answer is a clear no. Without controls, people with premarital partners are 161% more likely to dissolve their marriages compared to people who tie the knot as virgins. In other words, premarital sex increases the chances of divorce between twofold and threefold. After including the laundry list of covariates shown in the table, the odds of divorce remain 151% higher—in other words, a statistical artifact away from being identical.

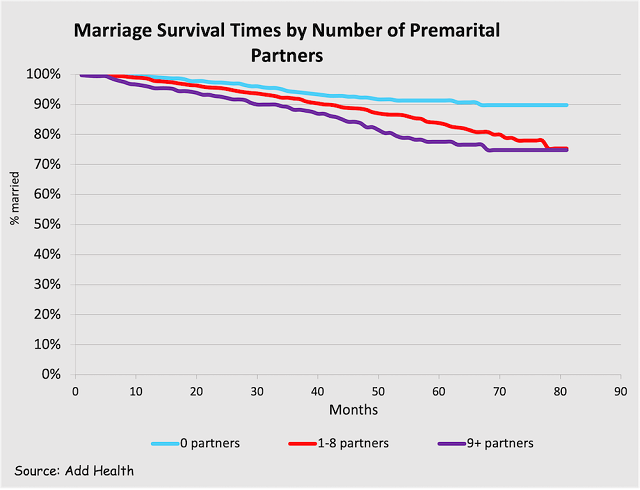

Few Americans marry as virgins these days. The median American man now has five lifetime partners, while the median woman has three. Our research shows that normative levels of premarital sex—between one and eight partners—still increase the odds of divorce, but only by 50 percent. The higher levels of divorce proneness are reserved for people who have nine or more partners, more common than people who marry as virgins but still a minority of Americans. These different divorce rates over marital duration are shown in the figure below. Moreover, these statistical relationships remain unaffected by the factors listed in the table.

The other finding of note is the absence of any gender difference in how premarital sex affects marital stability. This is surprising because of how different sex is for men and women. Men, of course, are more inclined to casual sex and more likely to exaggerate their sexual biographies. But none of that seems to matter, and we’re not sure why.

One way to frame our findings is as a null result: we were unable to explain the relationship between premarital sex and marital stability with a very wide range of measured factors. That’s not wrong, but we’re inclined to highlight how we’ve contributed to this longstanding question of social science interest: all of the posited factors other social scientists have pointed to as significant—religion, attitudes towards sex, and much more—do not hold up to empirical scrutiny.

This leaves two broad possible explanations for our results. One is that there could be a causal relationship here: having premarital sexual partners, especially a lot of them, does in fact undermine the prospect of a successful marriage. Perhaps as people accumulate partners, they find that breakups get easier, develop an “other fish in the sea” mentality, or move into peer groups with weaker marriage norms, any of which might make divorce seem like more of an option. The other possibility is that selection mechanisms might still be driving these differences, but we need to reconsider what those mechanisms are. Maybe there are genetic factors at work, or unmeasured psychological traits such as hypersexuality that contribute to both promiscuity and divorce. Our findings don’t resolve these questions, but we have defined the terrain for future research: scholars looking for the mechanisms linking premarital sex and divorce will have to look harder.

In another recent paper, Nick and Sam Perry showed that premarital sex partners have a causal impact on marriage rates, but a narrower focus reveals that the effect of premarital sex is limited to recent partners. Perhaps the effect of premarital sex partners on divorce is similarly constrained. Or perhaps not. It’s a question for future research. Either way, the current paper has shown that the conventional wisdom in this line of research will always benefit from empirical scrutiny.

Jesse Smith is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology and demography at The Pennsylvania State University. Nicholas H. Wolfinger is Professor of Family and Consumer Studies and Adjunct Professor of Sociology at the University of Utah. He is the author of Thanks for Nothing: The Economics of Single Motherhood since 1980, coauthored with Matthew McKeever, forthcoming from Oxford University Press.

1. We analyze two different Add Health subsamples. The first of these includes all respondents married at Wave IV of the survey. This sample lets us test whether myriad differences between respondents can explain the relationship between premarital sex and marital stability. The second subsample is limited to respondents who married after Wave III of Add Health. These respondents reflect adults who married after their mid 20s, enabling better measurement of their premarital sexual activity.